Heritage as Foundation for Future

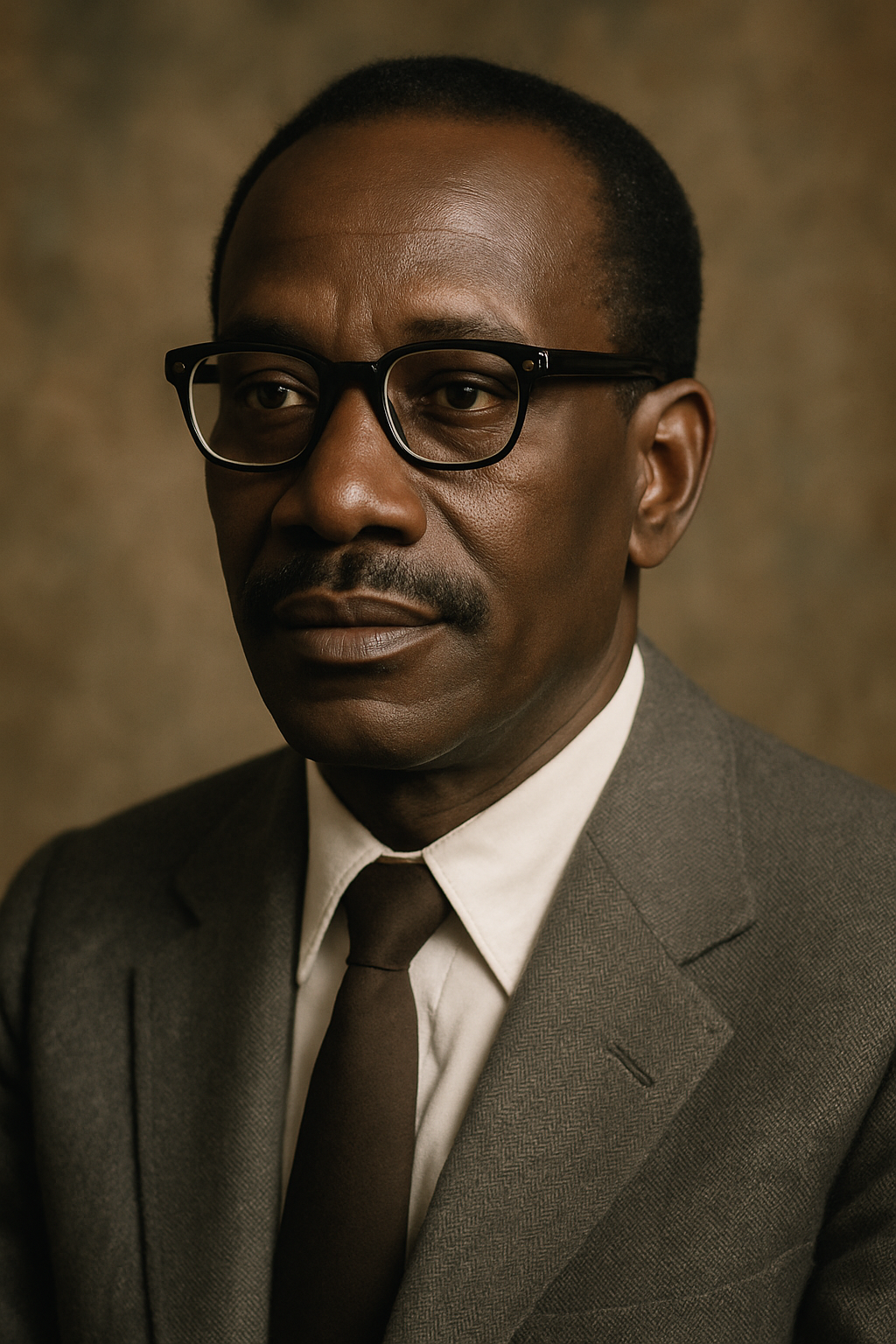

By Dr. Yosef ben Chochmah

For The Hebrew Scholar

Introduction: Building Tomorrow on Yesterday

Every people that survives centuries of oppression, exile, and forced forgetting does so because their foundation is anchored in heritage. Heritage is more than a record of the past—it is the mortar binding the stones of tomorrow. For the Hebrew people, whose journey has spanned Africa, Canaan, and the far reaches of the diaspora, heritage is not an ornament for nostalgia. It is the map that orients us, the compass that keeps us from drifting, and the root that ensures future generations bear fruit in their appointed season.

The task before us is not merely to preserve artifacts or rehearse memories. The task is to recognize heritage as an active foundation. It is the soil from which a resilient, self-aware, and divinely purposed people may rise again in strength.

Heritage as Covenant

When our ancestors stood at Sinai, they received more than laws—they received a covenant that embedded memory into destiny. That covenant was not about nostalgia but continuity. It bound fathers to sons, mothers to daughters, elders to youth.

Tanakh Witness:

“And thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt talk of them when thou sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down, and when thou risest up” (Deuteronomy 6:7).

This was not optional instruction. It was the survival strategy of a nation. Without covenantal remembrance, Hebrews would have been absorbed into the empires that surrounded them. With it, they endured—retaining language, law, and lineage even in captivity.

For today’s generation, covenant heritage means realizing that our future as a people depends not on assimilation into dominant cultures, but on fidelity to ancestral truth.

African Continuities: The Root Beneath the Trunk

Hebrew identity has always been intertwined with Africa. From the patriarchal journeys into Egypt, to Solomon’s encounters with Sheba, to the preservation of Judaic traditions among Ethiopian communities, Africa has never been a footnote to Hebrew heritage. It has been its cradle and its shelter.

Archaeological discoveries confirm these continuities. The Elephantine Papyri reveal a Hebrew military colony in Egypt. Nubian inscriptions mention alliances and conflicts with Israelite kings. Oral traditions in East Africa preserve narratives parallel to the Tanakh.

These continuities matter for the future. They remind us that our story is not a tale imported from elsewhere—it is a story deeply native to the soil of Africa. When we look to tomorrow, we must root our children not in borrowed identities but in the authenticity of who we have always been.

Heritage as Identity

Without heritage, identity dissolves. In times of exile, colonization, and forced assimilation, oppressors have understood this truth well. By severing a people from their past, they cripple their future. But our ancestors resisted.

They encoded memory in song. They preserved sacred names through whispered prayers. They kept rhythms of Sabbath and harvest even when stripped of land. They passed fragments of Hebrew language, customs, and worldview into the marrow of future generations.

Tanakh Witness:

“If they shall bethink themselves in the land whither they were carried captives, and repent, and make supplication unto thee… then hear thou their prayer” (1 Kings 8:47–48).

Heritage is the act of “bethinking”—remembering who we are in the land of strangers. It is the compass that realigns us when oppression tries to scatter our direction. For a people often told they are invisible, heritage says: you are eternal.

Living Heritage: From Festivals to Family Practices

Heritage is never abstract. It lives in the way families gather, the way elders teach, the way stories are told, the way festivals are observed.

Pilgrimage festivals of ancient Israel were not just religious rites—they were nation-building events. They connected agriculture to theology, land to liturgy, and household memory to national destiny. Excavations of storage jars, altars, and inscriptions show that ordinary families, not just priests, carried this work forward.

In the diaspora, the equivalent is family-centered remembrance. A Sabbath meal becomes more than food—it becomes reenactment of covenant. A child’s naming ceremony becomes not only cultural but covenantal. Oral storytelling turns living rooms into sanctuaries.

To build a future, we must not only document heritage but embody it in homes, schools, and communities.

Heritage as Resistance to Erasure

Empires destroy by erasing memory. Assyria dispersed tribes, Babylon burned scrolls, Rome outlawed covenant practices, and later colonizers rewrote maps and genealogies. Yet heritage persisted.

Tanakh Witness:

“Remove not the ancient landmark, which thy fathers have set” (Proverbs 22:28).

This verse is not merely about physical property lines. It is about cultural and spiritual boundaries. When nations sought to move the landmark of our identity, our ancestors resisted by holding fast to Torah, to oral tradition, and to family memory.

Today, the erasure comes in new forms: consumer culture, miseducation, historical revisionism. But the principle is the same. Heritage is resistance. By holding fast to ancestral ways, we declare: we cannot be erased.

Heritage and Innovation: Continuity Without Stagnation

Some imagine that heritage belongs to museums and innovation belongs to the future. But in Hebrew thought, these are inseparable. The wisdom of yesterday fertilizes the soil for tomorrow’s creativity.

Tanakh Witness:

“Stand ye in the ways, and see, and ask for the old paths, where is the good way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls” (Jeremiah 6:16).

The “old paths” are not obsolete—they are guideposts. They ensure that new inventions do not sever us from who we are. In this way, heritage becomes not a chain but a springboard.

Future technologies, community structures, and cultural expressions will succeed only when they remain grounded in ancestral truths. Otherwise, they risk becoming rootless and unstable.

Heritage as Communal Responsibility

One person cannot carry heritage alone. It belongs to the collective. Elders teach, youth inherit, and leaders safeguard. Heritage becomes the invisible infrastructure of community life—shaping values, informing ethics, and guiding decisions.

Archaeological evidence of communal storage facilities, shared wells, and public inscriptions in ancient Israel illustrate how heritage was preserved by collective effort. One family could not preserve an entire festival, but the nation together could.

In our day, heritage as communal responsibility means building schools that teach truth, forming cultural institutions that preserve memory, and creating intergenerational spaces where wisdom flows freely.

Steps Toward Future-Building

-

Teach History Honestly: Root children in Hebrew-African continuity.

-

Preserve Language: Promote Hebrew study alongside African tongues.

-

Practice Festivals: Let annual rhythms shape communal identity.

-

Empower Elders: Elevate elders as carriers of wisdom, not sidelined voices.

-

Strengthen Families: Build homes where Hebrew values are daily practice.

-

Create Cultural Media: Literature, film, music, and art must reflect Afro-Hebrew identity.

-

Build Economic Independence: Heritage is weakened without self-sustaining community economies.

These steps ensure that heritage is not ornamental but foundational for generations ahead.

Conclusion: Tomorrow Rooted in Yesterday

Heritage is not a relic—it is a foundation. Without it, the Hebrew future would crumble under the weight of assimilation and forgetfulness. With it, we rise resilient, carrying the memory of our ancestors into the promise of tomorrow.

Tanakh Closing Word:

“Remember the days of old, consider the years of many generations: ask thy father, and he will shew thee; thy elders, and they will tell thee” (Deuteronomy 32:7).

The wisdom of our ancestors is not simply history—it is prophecy. It tells us that the only way to move forward is to stand firmly upon the stones of yesterday. For Afro-Hebrews today, this is not optional. It is destiny. Heritage is our foundation, and upon it the future must be built.

Selected References

-

Dever, William G. Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. SBL Press, 2017.

-

Diop, Cheikh Anta. Civilization or Barbarism. Lawrence Hill Books, 1991.

-

Kitchen, Kenneth A. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Eerdmans, 2003.

-

Yamauchi, Edwin. Africa and the Bible. Baker Academic, 2004.

-

Wright, G. Ernest. The Old Testament Against Its Environment. SCM Press, 1950.