Archaeological Treasures of Hebrew Heritage

By Dr. Amara ben-Yisrael

For The Hebrew Scholar

Introduction: Stones that Speak

Throughout history, the descendants of Israel have often been told their story through the voices of others. Yet in the dust of the Near East and the soil of Africa lie testimonies that neither colonial theologians nor revisionist historians can erase. Archaeology, the study of material remains, provides us with tangible evidence of the Hebraic presence—remnants that speak across millennia, confirming and illuminating the accounts preserved in the Tanakh. These archaeological treasures are not the relics of strangers but the heritage of a melanated people whose roots stretch deep into both Africa and the ancient Levant.

The seven-branched menorah, carved upon stone and etched in memory, stands as the emblem of our identity. Beyond the pages of Scripture, spades in the earth have unearthed royal inscriptions, household vessels, temple remnants, and even songs carved in stone. These findings affirm what Deuteronomy, Isaiah, and Kings already testify: Israel was a real people, melanated, dwelling between Africa and Asia, shaping and being shaped by the currents of history.

Africa and the Ancient Hebrews: A Shared Landscape

Before examining specific discoveries, we must establish geography. The biblical world is not confined to the borders of modern Israel. Egypt, Cush, Nubia, Ethiopia, and the Sinai were integral to Israelite history. Abraham sojourned in Egypt (Genesis 12:10), Moses was raised in the Egyptian court (Exodus 2:10), and the Exodus itself was a movement of peoples across African and Semitic boundaries. Thus, it is no surprise that archaeology finds Hebrew footprints not only in Canaan but also along the Nile and in lands southward.

African archaeologists, such as Cheikh Anta Diop, have argued persuasively that one cannot understand the Semitic world apart from its African cradle. This perspective recovers Israel from the whitening lenses of medieval Europe and returns the Hebrews to their rightful place as a melanated Afro-Asiatic people.

The Merneptah Stele: Israel’s First Mention

One of the earliest external references to Israel is found in Egypt. The Merneptah Stele, dating to around 1208 BCE, describes Pharaoh Merneptah’s campaigns in Canaan. The hieroglyphic inscription boasts: “Israel is laid waste; his seed is no more.” While intended as Egyptian propaganda, the stele proves Israel’s presence in the land by the late 13th century BCE. The determinative sign used indicates Israel was not yet a kingdom but a people—a tribal confederation recognizable enough to be named among Egypt’s enemies.

For Afrocentric Hebrews, this discovery is significant. It places Israel firmly in the Egyptian orbit, reminding us that the Hebrew people and African civilizations were contemporaries, interacting in trade, war, and migration. The stele also aligns with Judges 1, which describes tribal skirmishes before Israel’s monarchy.

Tanakh Connection: “So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that YHWH said unto Moses; and Joshua gave it for an inheritance unto Israel” (Joshua 11:23).

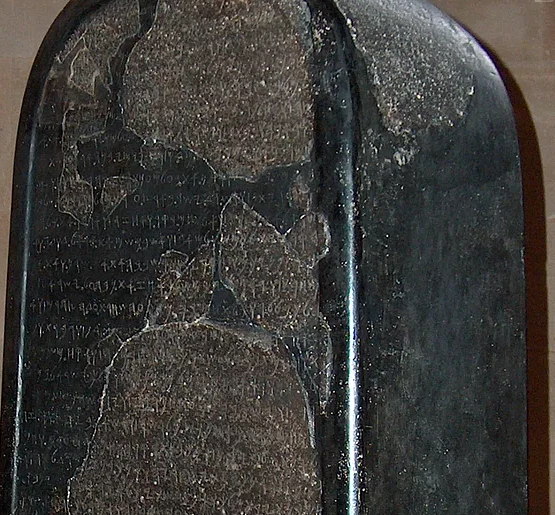

The Mesha Stele: House of David Confirmed

Another monumental find is the Mesha Stele, discovered in 1868 in Dhiban (ancient Moab, modern Jordan). This basalt stone records King Mesha of Moab’s rebellion against Israel in the 9th century BCE. What makes it invaluable is its reference to the “House of David.” Critics once doubted David’s historicity, relegating him to myth. Yet this Moabite inscription, corroborated by fragments from Tel Dan, affirms David as a dynastic founder whose descendants ruled in Jerusalem.

For Afro-Hebrew heritage, the Mesha Stele serves as a corrective. The great King David—shepherd, warrior, poet—was not a pale medieval construct but a dark-skinned man of African-Asiatic descent. His dynasty was carved not only in Scripture but in stone left behind by his enemies.

Tanakh Connection: “And David the son of Jesse reigned over all Israel. And the time that he reigned over Israel was forty years” (2 Samuel 5:4).

The Siloam Inscription: Voices from Hezekiah’s Tunnel

Moving inside Jerusalem, the Siloam Inscription (8th century BCE) records the completion of King Hezekiah’s water tunnel, built to secure Jerusalem’s water supply against Assyrian siege. Carved in ancient Hebrew script, it describes how two teams of diggers tunneled through solid rock until they met in the middle. This engineering marvel, confirmed by both text and archaeology, is described in 2 Kings 20:20.

What makes this treasure profound is that it is not a royal boast but a communal memory. Workers—Hebrew laborers with dark, calloused hands—recorded their triumph in their own script. Their words still echo from the limestone tunnel beneath Jerusalem, a reminder that common Hebrews were literate, skilled, and historically real.

Tanakh Connection: “And the rest of the acts of Hezekiah, and all his might, and how he made the pool, and the conduit, and brought water into the city, are they not written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Judah?” (2 Kings 20:20).

Lachish Reliefs: Hebrews in Assyrian Eyes

The walls of the palace at Nineveh, capital of Assyria, bear carvings known as the Lachish Reliefs (c. 701 BCE). They depict King Sennacherib’s conquest of the Judean city of Lachish. In these panels, we see Hebrew men, women, and children—dark-skinned captives being led into exile, defenders executed on stakes, and households carried away.

While the images are grim, they confirm the biblical account of Assyrian aggression (2 Kings 18). They also provide visual testimony that the Israelites, like their neighbors in Canaan and Egypt, were melanated. The Assyrian artists who carved them had no incentive to flatter Israel—they simply portrayed what they saw. Their art is our vindication.

Tanakh Connection: “Now in the fourteenth year of king Hezekiah did Sennacherib king of Assyria come up against all the fenced cities of Judah, and took them” (2 Kings 18:13).

The Elephantine Papyri: Hebrews in Egypt Again

In the 5th century BCE, long after the Babylonian exile, a Jewish military colony lived on Elephantine Island in southern Egypt. Their correspondence, preserved on papyri, describes a functioning temple dedicated to Yahu (YHWH), alongside the worship of Anat, an ancient goddess. These documents reveal not only the persistence of Hebrew communities in Africa but also the complexity of their faith and cultural adaptation.

For African Hebrews today, Elephantine proves our ancestors were not confined to Judah or Babylon. They served in garrisons, built temples, intermarried, and maintained Hebrew identity along the Nile. The diaspora was not just a later Greco-Roman phenomenon—it was already unfolding in antiquity.

Tanakh Connection: “In that day shall five cities in the land of Egypt speak the language of Canaan, and swear to YHWH of hosts” (Isaiah 19:18).

The Ketef Hinnom Scrolls: Blessings in Silver

In 1979, archaeologists discovered two tiny silver scrolls in a tomb near Jerusalem. When unrolled, they revealed inscriptions of the Priestly Blessing from Numbers 6:24–26. Dated to the 7th century BCE, these scrolls contain the oldest known biblical text. Long before the Dead Sea Scrolls, Hebrew words were already being worn as amulets—sacred verses inscribed on precious metal.

The discovery affirms the antiquity of Hebrew scripture and its use in daily life. For the descendants of Israel, it is evidence that the blessings we recite even now—“YHWH bless thee, and keep thee”—were cherished by our ancestors three millennia ago.

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Hidden in the Wilderness

No survey of archaeological treasures would be complete without the Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in the caves of Qumran beginning in 1947. These texts, ranging from 3rd century BCE to 1st century CE, preserve nearly every book of the Tanakh, alongside sectarian writings. They demonstrate the continuity of the Hebrew text and the spiritual ferment of Second Temple Judaism.

From an Afrocentric perspective, the Scrolls highlight that the custodians of Israel’s scriptures were not medieval monks in Europe but melanated Hebrews dwelling near the Dead Sea. Their parchment and ink, sewn together with sinews, represent devotion, scholarship, and the determination to preserve identity in the face of empire.

Tanakh Connection: “Seek ye out of the book of YHWH, and read: no one of these shall fail” (Isaiah 34:16).

Archaeology in Africa: Nubia and Beyond

While many treasures are found in Canaan, African soil too preserves Hebrew echoes. Nubian records mention contact with Israelite kings. The Ethiopian Kebra Nagast recounts traditions of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba—stories resonant with biblical accounts (1 Kings 10). Archaeological excavations in Axum and other Ethiopian sites reveal a long-standing Judaic presence, evidenced by inscriptions, ritual objects, and enduring Beta Israel communities.

From the fortress of Elephantine to the highlands of Ethiopia, the archaeological record confirms what Deuteronomy 28:68 foresaw: Hebrews dispersed, mingling with African peoples, leaving traces in both text and soil.

Conclusion: Stones Cry Out

Archaeology does not replace faith, but it affirms memory. Each inscription, relief, and scroll is a witness that the children of Israel walked this earth, melanated and mighty, their lives intertwined with Africa and the Levant. These treasures are not merely relics for museums—they are inheritance for a people awakening to their identity.

As Yahshua once declared that if the children held their peace, “the stones would cry out” (Luke 19:40, though we do not rely on the New Testament for authority), archaeology is precisely that: stones crying out. They cry out against erasure, against whitening, against exile without return. They testify to our covenant, our endurance, and our hope.

The challenge before us today is to preserve these testimonies, to teach them to our children, and to walk upright knowing that archaeology itself proclaims: Israel lives.

Selected References

-

Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001.

-

Diop, Cheikh Anta. The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1974.

-

Finkelstein, Israel & Silberman, Neil Asher. The Bible Unearthed. New York: Free Press, 2001.

-

Kitchen, Kenneth A. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

-

Pritchard, James B. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969.

-

Tigay, Jeffrey H. Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.

-

Yamauchi, Edwin. Africa and the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004.